Are We Free

Another Discourse On An old Subject

The term “freedom,” appears throughout the annals of human history as something real, almost tangible, its perceived manifestations wide and varied. We all believe in freedom and relish it. I would go so far as to say that the idea of freedom, in one form or another, is an integral part of most, if not all, cultures. Most often we hold very concise preconceptions of specific freedoms we believe ourselves entitled to and rail against those that might dare impugn these. And, at times, we are often unaware of our notions of freedom, until someone, or something, quite often an institution, takes steps that waken us to the possibility that something might be taken away from us and then define that thing as a freedom.

The overarching issue that becomes apparent in delving in to freedom, as a concept, or even an ideal, is that there are a plethora of views, often conflicting, on what it actually encompasses. While there is a kind of general acceptance that everyone is entitled to freedom, when applied, the term is more often than not used to describe an individual right or one that inures to a specific interest group, even if at some cost to the freedom of another. Hence, in order to explore the question I have posed here, whether freedom is a real thing, it seems prudent to arrive at a definition of the term, a benchmark, if you will, from which to launch an inquiry. For that purpose, and without overly delving into the multitude of philosophical treatises that have been aimed at the discussion over the millennia, the Oxford English Dictionary, or OED, will serve as a foundation.

According to the OED, the salient attributes of freedom are an “Exemption or release from slavery or imprisonment; personal liberty,” and, “the quality of being free from the control of fate or necessity; the power of self-determination attributed to the will.” The former is expressed as including literal and figurative slavery or imprisonment, while the latter is exemplified by the OED through a passage from John Locke's, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, dated 1690, in which he wrote, “In this, then, consists freedom, viz. in our being able to act or not act, according as we shall will or choose.” Collectively, then, these definitions find coalescence in Locke's position, found in his Second Treatise of Government, published in 1689, that,

. . . what state all men are naturally in, and that is, a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons, as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature, without asking leave, or depending upon the will of any other man.”

Importantly, in this passage, Locke distinguishes the limits of freedom between those that are naturally ordained and any human artifices that expand thereon. To Locke, as made abundantly clear throughout his writings, natural law is divinely ordained morality, innately manifest in the ken of every human. Though seemingly anarchistic at first blush, Locke was by no measure advocating ungoverned chaos. Instead, as expressed in his Second Treatise, he posited that social institutions must simply be barred from intruding into matters held sacrosanct within the parameters of natural law in their rule making authority in order to retain legitimacy. This view was subsequently adopted by Thomas Jefferson, indisputably evidenced in his drafting of the opening to the United States' Declaration Of Independence, of July 4th, 1776, which reads:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal and independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent and inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these ends, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government shall become destructive of these ends, it is the rights of the people to alter or to abolish it, & to institute new government laying it’s foundation on such principles and organizing it’s powers in such forms, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness

Express in these connotations of freedom is the specter of consequences for those institutions whose dominion encroaches on individual rights of conduct prescribed by the law of nature. Implicit, is that the freedoms of individuals are likewise subject to repercussion if their exercise of these violate the moral imperative. Thus, we arrive at a conundrum; how am I to know which exercise of my right to freedom is morally acceptable. If natural law has its basis in morality, the questions are begged as to how and by whom morality should be defined, and how are we to distinguish natural law from its artificial nemesis.

Resolving these is made all the more nebulous if done through the lenses of Locke, Jefferson and the like, whose foundations were mired in Christianity, itself the very basis for their understanding of morality. This dilemma extends to the thought processes of every person whose roots lie in a sense of morality that is institutionally derived, be it Buddhist, Islamic, Jewish, Shamanistic or Statist. Even Karl Marx, a self-avowed enemy of “morality,” posited the virtues of self development and ownership of the fruits of one's labors, on a collective basis, as ideals of Communism and thus described his vision of morality, albeit couched in different terms.

The common thread here is that regardless of the wellspring of morality, whether of innate knowledge from birth or other circumstances, it is a concept that has required interpretation and definition. Moreover, this task has invariably been undertaken by some form of institution and has often justified the genesis of their creation, particularly those that are religious. In essence, then, whatever the specters of innate circumstances or natural law may suggest, these succumb to arbitrary interpretation and codification in some form or another. And, as with any human construct, the results often prove fluid, dependent upon the caprices of societal influences, or the exercise of extrinsic motivations on those institutions that have taken ownership of morality.

Hence, we have seen the purported ideals of Siddhartha and Jesus transformed into Buddhist dogma and the Bible, respectively; the “anti-moral” ethics of Marx converted into the canons of the communist state; and, Thomas Jefferson's adoption of John Locke's principle, that the rights of man nestle in the protections of natural law, as sanctified in the United States' Declaration of Independence, reshaped as the United States' Constitution, wherein no mention of “natural law” is to be found. And, the latter remark is indeed indicative of the norm in all transitions from concepts of freedom to their memorialization and, ultimately, their implementation.

Thus, I wonder whether Siddhartha would have embraced veneration of the Dalai Lama as the spokesperson for a belief system he had no intention of institutionalizing. Similarly, despite what little we know of Jesus' concepts of virtuosity and individual freedom, it seems we know enough to raise questions as to whether he would have supplicated to the trappings and wealth of the Catholic church, and its ilk, all claiming divine edicts to assume the roles, often competing, as sole arbiters of God's will and policing the limitations on freedom demanded by Him - as interpreted by church doctrine. Would Marx, in spite of his authoritarian bent, have recognized the enslavement of millions, save the ruling elite, trapped in communist regimes, such as the former USSR and the present Peoples Republic of China, as manifestations of his ideology. And here, in the United States, where we took a running leap from the Declaration of Independence, bounced on the Constitution and plunged into a morass of legislation and judicial interpretations, would Locke laud the flabbergastingly corrosive effect of these on his principle of people's rights to enjoy “a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons, as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature, without asking leave, or depending upon the will of any other man.”

In spite of the enshrinement of liberty interests in the U.S. Constitution, under the aegis of the majority of the Amendments thereto, the freedoms of speech, the press, religion, assembly, to bear arms, together with various protections from encroachments by government on individual liberty interests, time has shown that these freedoms are not sacrosanct. Legislation, judicial interpretation and shifting societal mores have each, in their own way, reshaped both the concepts of natural law, or morality. Quite notably, where John Locke proclaimed the ownership of private property and the right to rebel against any government that abused the rights of its constituents, as fundamental attributes of natural law, a sentiment echoed by Thomas Jefferson, these were effectively eliminated by the eventual imposition of taxes on private property and the characterization of rebellion as seditious, and therefore illegal. I would suggest that these two shifts alone, represented a return to the feudalism, albeit in more sophisticated form, so abhorred by Locke, and which served to compel many of his beliefs. Americans, as must the denizens of most countries, may hold property in fee, but are expected to be sufficiently productive to pay taxes thereon, or lose their property. So too, are they required to pay taxes on their incomes and remain loyal to their liege, modernly speaking, the State.

Predictably, and inescapably, it also bears mentioning that conflicts have arisen over interpretations of morality and the consequences for breaching its post interpretation standards within supposedly unitary systems. A prime example of this exists within the framework of inter-governmental relations between the United States government and tribal nations located within the U.S. The latter, by and large self-governing, have sought to codify their own cultural mores as a standard of expected conduct and, while not fully at odds with those throughout the remainder of the country, as to basic sins, such as murder, the federal government's insistence on the application of its interpretation of its Judeo-Christian moral roots, as the font of any rights enjoyed by those groups, has certainly led to the impositions of standards alien to traditional native cultures, both in terms of conduct and, even more so, as applied to the punishments for transgressions.

Similar dichotomies appear in the present Covid pandemic experience in the United States, where federal courts, ruling on government mandates against gatherings, seen to exacerbate the spread of Covid, saw no contradiction in striking down fiats forbidding people from attending churches, while upholding bans on weddings, concerts and gatherings in restaurants and bars.

A further evolution in institutional interpretations that merits scrutiny is the increasing propensity to shift from individuals being left to their own devices, as a moral right, towards interfering in such by assuming a patriarchal, or matriarchal, if you will, role in the lives of people by subsuming personal responsibility with a structure that purports to take care of the individual by assuming we are incapable of doing so for ourselves. Hence, we have laws that prohibit the use of certain drugs, it is illegal to jay-walk and participation in government schemes, such as social security, is mandatory. In essence, self-sufficiency and personal responsibility are being rendered morally obsolete.

The sum of the foregoing is not offered by way of judgment, on my part, but rather as a mosaic to illustrate the point that whatever our state at birth, be it some form of moral purity that is determinative of our rights, or with liberty interests endowed institutionally, we have no say in the breadth or depth of these – at least as extrinsically defined and applied. These interpretations lie in the hands of shamans, and their counterparts throughout history, to be then tribally adopted as expected modicums of conduct and, ultimately, as regulatory schemes for enforcement purposes. It also stands to reason that these processes are influenced by a number of factors, including less than ideological motivations, such as control, and the effect of precedents in shaping the outcome.

More to the point, all I have described in the preceding paragraphs draws me to the inescapable conclusion that we are subject to at least one layer of limitation to our freedom; that extrinsic circumstances, particularly those of dominance, establish paradigms which dictate that the exercise of our free will, where contrary to the codification of morality, and regardless of our acquiescence, carries risks of consequences which may well include stigmatization, loss of property interests, incarceration or even one's execution – depending on the nature of the transgression and the attendant penalties. All of this said, the mere fact that while repercussions, if we act against the establishment grain, may serve to inhibit our willingness to act, these do not thwart our actual ability to exercise such freedom. Thus we are still free to act in accord with our wills or desires. Logically, then, the next predicament we must face is whether we are free willed, given that the right to choose becomes relatively meaningless if the choices we imagine are not freely crafted by us.

This question delves into the heart of freedom as a thing.

As a side note, there are certainly a plethora of inhibitions to our freedoms, that we are either compelled to obey, or must choose to accept, other than those arbitrarily imposed upon us by our forebears and present brethren. We are bound to operate within the bounds of Newtonian physics, at least until future discoveries in the quantum world allow us to escape these. We must choose sustenance, air and water to nourish us, or we will die. We cannot fly of our own accord, because we do not have wings, though distant genetic or bio-mechanical engineering advances may eventually alter this reality. So, we must now accept that our freedoms are curtailed, and even sometimes denied, not only within the scope of our institutional realities, but also as a result of our environmental and physical landscapes. But, none are as limiting as would be an incursion into our free will; the freedom to craft our choices without influence or interference.

My arrival in the womb was arbitrary. I had no say in the matter; no freedom to offer a thumbs up or down to the event that led to my being. Even to my parents, it was an “Oops” moment, an unintended consequence of another choice they had made. And then, what? Here I was, percolating along, a mishmash of genes and subject to my mother's moods and actions, the shock of pregnancy, the booze she drank and foods she ate, as examples, and the noise from without, languages spoken, music, singing, laughter, arguments, discussions, and the like. There is more than mere suggestion that all of these influences, conspired, at least in part, to shape the being I would manifest, once flung onto the exit, the offramp leading to reality and the personality I would evolve. Those formative months in the womb, then, to follow me, unbidden and unchosen, to the tomb. Indeed, multiple studies have affirmed such influences, genetic and environmental, on the postnatal characters we become; nature and nurture shaping the mold from which we emerge, inheritances and bequests that continue to shower us throughout our formative years. And, if the influences on us before childbirth are akin to the patter of a light drizzle, it would be safe to say that we are deluged, from birth through our youths, with environmental stimuli that are the music to which our inherent natures learn to dance.

We are raised within the ethos projected by those we are answerable to under the circumstances of our upbringing, whether idyllic “Leave It To Beaver” settings, orphanages, single parent environments, homeless shelters, blended family homes, or whatever else these might be. So too, are we swayed by the environment in which our guardians find themselves and that they themselves have created as a result of both circumstance and purpose. All these, save happenstance, perhaps, the culmination of their own natures, natal and post natal experiences. Were this insufficient, we are further subjected to siblings, full, half and step; peers; teachers; family friends and acquaintances; doctors; dentists; and, perhaps, for some of us, policemen, with each encounter having some bearing on our formative years.

Anecdotally, and by way of example, I grew up in a tumultuous, authoritarian household. My father was a German of Swedish descent, my mother German. He grew up in Berlin and longed for a rural existence and my mother spent many of her formative years on a farm. They eventually bought a ranch in the hinterlands of British Columbia, where we moved from the city during my tenth year. Both insisted on speaking German in the house and, in spite of having been born in Canada, this was my first language and English, which I learned at school and on the streets, my second. My three half siblings were not subject to this demand, residing, most of the time, with their mother, who was less inclined to thusly punish them – my sentiment at the time. And, by the time my two younger siblings came along, my parents' stance had softened considerably. World War II was yet a fresh wound on the urban Canadian psyche during my early childhood and the adult hatred of Germans was indelibly imprinted in the minds of the children who were my peers. Hence, daily ass whuppins', as it were. Some I gave, most I received, particularly when confronted with more than one assailant at a time, all bent on avenging the Allied cause, not infrequently in the presence of unsympathetic elementary school teachers. Slang also presented lessons to be learned. Eager in my hope of making friends, I once volunteered to be the “injun” in a game of, yes, “cowboys and injuns,” and on being tasked with the role, immediately charged about emulating the sounds I believed a train engine would make, perhaps a rarely justifiable grounds for another “ass whuppin.”

It was not until we moved to the country that I found peace and solace - in the woods, mountains and in the inhabitants of our village, comprised of immigrants from various parts of Europe and people who were too busy farming, logging and ranching to rehash the past. So too, was I employed in these endeavors, although that term may be somewhat euphemistic given the dearth of remuneration, often at times that conflicted with my formal schooling and ever accompanied by my father's mantra, “never let school interfere with your education.” This, followed by his bewilderment when I skipped classes to follow my yearnings, rather than his demands. Our place was some ten miles from town and that distance, coupled with my familial obligations, rendered social intercourse difficult at best. Suffice it to say, I did a lot of walking.

My half siblings, although there were sporadic interludes of relative peace, and even happiness, in their company, tended to transfer their hatred of my mother, who they saw as the instrument responsible for the demise of my father's marriage to their mother, towards me. They were, of course, only half right and completely oblivious to the lack of choice I had in the manifestation of my being. My father never intervened in these events, likely prevented from doing so by a sense of guilt which, at the time, I saw as a form of abandonment. And, in turn, I resented the appearance of my younger siblings, some years after I was born, who represented not only competition and another responsibility, but were treated without the harshness that was a hallmark of my youth.

Blue. My mother insisted on blue shirts. And, black oxford shoes.

Relatives, other than my immediate family, were a rarity in our household. My father was close to his sister and remained in contact with his father, who traveled to live with us for a year before going back to the old country where he felt more comfortable. It was only until I was in my early teens that I learned my father had some half dozen half siblings with whom he had ended all contact. I would learn, subsequent to his visit, that my paternal grandfather also had severed all ties with his siblings over some, I suspect, long forgotten slight. Ultimately, the reasons behind my father and his father ending those relationships have remained a mystery. My mother was more inclined to stay in touch with her two sisters, with whom she feuded on regular basis, and parents, who came to visit, just as she would travel to Germany to visit with them. Both of my parents drew express and clear contrasts between the people in their lives who were deemed to be acquaintances and the less than a hand full who were accorded the stature of friends. The former would simply disappear from my awareness radar, sometimes after many years, and even a couple of the latter were not immune from being shunted out of my parents' lives. I was never a participant in my parents' social activities, even in our home. Conversely, my half siblings were included in their mother's social circles, which overlapped extensively with those of my parents, and often struck up friendships with the progeny of her friends and acquaintances.

My father drank copiously, though never appeared to be effected, until, in his late seventies, he quit drinking altogether, after an incident that brought him to the realization that his body could no longer process alcohol as it once had. My mother was a typical Jekyll and Hyde drinker. Both smoked heavily. And, as a final note, although I would learn that my mother harbored some prejudices during my later years, religion, race and ethnicity were never discussed in our household. My father, in particular, accepted every person he encountered, openly and at face value. His view on religions was simply that these were questions of personal choice, among the many matters left to each of his children to decide upon, if and when we elected to do so.

Throughout the years of my upbringing, encouraged by my parents and solitude, I found constant companionship, as I do to this day, in books. Cervantes, Kerouac, London, Conrad, L'Amour, Brand, Melville, a few of the many I sought out, introduced me to characters who became heroes, friends, inspirations and provided moral compasses, in addition to the ethics imposed by my parents. Interestingly, on reflection, many of these protagonists were loners, generally possessed of a romantic bent, and oftentimes, misfits.

By the time I reached the age of fifteen, I had had enough. Bound and determined to

write my own story, I set off, hitchhiking and working my way around the country. Over the years I would return to the fold, as it were, from time to time, for relatively short periods of time, but remained generally on my own, doing my thing. I went to sea, fishing for king crab, herring and salmon; earned my master mariner's ticket, and drove everything from small tramp freighters to tug boats and salvage vessels. Ultimately, I earned my GED, my undergraduate degree and, finally, during my late forties, a law degree. As an adult, my long standing rebellion having come to a close, I became closer to my father than I had during my younger years. I made more frequent visits to the ranch, the only place I had recognized as a home, and we spoke on the telephone most Sundays, enjoying conversations about all manner of subjects. When he died and the ranch was sold, I felt an immediate disconnection from that place and the people I had grown up with which has remained with me to this day.

Save for the present purpose, this synopsis of my life's story is irrelevant, a tougher childhood than some experienced but, in the grand scheme of things, far easier than those of most people. The pertinent question here is whether these past experiences are determinative of my present abilities to exercise freedom of choice in executing my decisions. A goodly portion of the answer lies in the person I have matured into, provided my assessment is honest. I will, in spite of my aversion to navel contemplation. endeavor to meet that requisite objectively.

Let me begin by saying that I do not own any blue shirts. And, save on the rarest of occasions, usually of a formal nature, I have not worn shoes for fifty years, save when formal occasions have required it. Instead, I wear sandals.

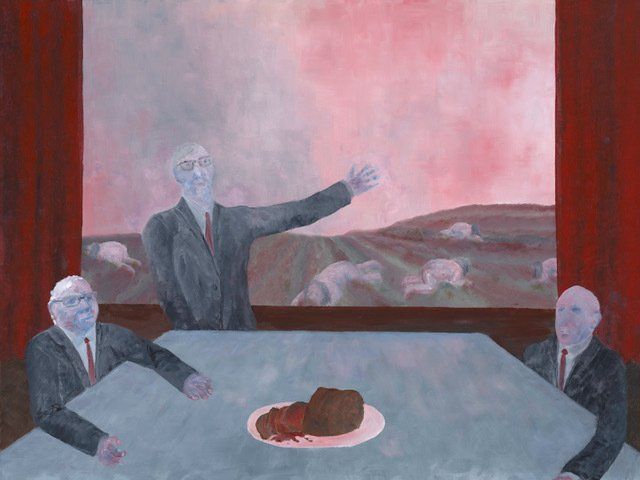

I take everyone I meet at face value, regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, gender and financial wherewithal, which I can say with all honesty I tend not to notice, although I do withdraw from people who make it a point to demand special consideration as a result of any one of these conditions. Nonetheless, I am ill inclined to trust people, my tendency to keep most relationships at arm's length. Indeed, I can say that I enjoy solitude and find that being alone is worthy of embracement rather than lamentation. As did my forbears, there is to me a great distinction between friends, of which I have very few, and acquaintances and without remorse I have ended relationships for a variety of reasons. Indeed, I am fully estranged from what remains of my immediate family, of mind that, with the absolute exception of my children, whom I love unconditionally, the people I choose to have in my life, and who do likewise with me, are of far greater importance to my happiness and well being than those whose sole commonality with me is a familial blood line. And, while I do not miss any of these people, the romanticized notion of breaking bread with a large, multigenerational family and close friends at a large outdoor table in the south of France, or Italy, or Spain, and whose loyalty and support is unwavering, does have a compellingly strong appeal. Thus, while I am inclined towards films depicting murder and mayhem, Russel Crowe's “A Good Year,” remains an idyllic favorite.

My nature remains nomadic and rebellious, my mind curious, though impatient, and I believe wholeheartedly that our raison d'etre is to continually strive towards acquiring ever more knowledge, lest the spaces we inhabit are wasted. What others think of me is of no interest. I prefer small social gatherings, shunning large parties, and prefer conversation to breach the taboos of American politeness, by diving readily into international affairs, political economy, religion and, yes indeed, the latest thoughts in quantum physics. Finally, I am consistently disillusioned by my perception that neither I nor the world in which I find myself can meet my highly romanticized and idealized notions of ethical conduct and that our chosen efforts will be measured or judged solely within the framework of a pure meritocracy.

In my opinion, albeit of the lay variety, the influences we endure during the “nurturing” phase of our lives, do not bode well for any notion that free will, and the choices we derive therefrom, exists in a vacuum free of any intervention, or even interference, by the extrinsic influences that precede our choices throughout life. Furthermore, it seems that such precedents pervade our decision making processes regardless of whether these represent conformity thereto or are reactionary. I think it important to point out that most of the choices I have made were not undertaken with some conscious awareness that suggested I either adopt specific nurturing events or rebel against them - it is only retrospectively that I now am able to see how these influences served to shape the bulk of my decisions. That said, of additional note, and I think consistent with normal behavior, it should be said that some of my choices were made with full cognizance that these represented endorsement or rejection of my childhood experiences. For instance, my approach to child rearing was a deliberate adoption of the positive methods employed by my parents and a rejection of those I disagreed with. Yet, somewhat ironically, I have caught myself in the throes of emulating one or the other of them, without any conscious awareness of doing so.

Were the effects of nurture not sufficient to somewhat shake our confidence in the notion of free will, there are other plausibly influential factors worthy of some consideration. Environmental conditions certainly play a role as well. War and peace, poverty and wealth, hot and frigid climates, rural environs and those of an urban nature, crime and security, majorities and minorities (regardless of whether this is represented by racial, ethnic or any other form of actual or latent dominance by any group) and economic booms or busts, are but some of any number of examples that would qualify as environmental conditions that could, and do, fashion the choices people make.

The Great Depression of the 1930's, for example, spawned a generation of people who openly adopted frugality as a countermeasure to thwart future economic uncertainty, the tenets of which were passed down to the subsequent generation, to ultimately dissipate with future series of progeny, when the memory of that travesty had faded from public consciousness. Inner city youths develop clearly different outlooks than those of children raised in more affluent areas. Child soldiers, numbering some 300,000 throughout the world, oftentimes forced to kill their own parents in order to themselves be spared, are traumatized in ways unfathomable to children not subject to similar horrors. The outlook of people sold today into slavery in a Libyan market must, by definition, lie in direct opposition to that of those who purchase them. In Germany, in the wake of the Reichstag fire of 1933, Germans welcomed Hitler's suspension of the Constitution in the interest of personal security, much as Americans fully accepted, then president, George W. Bush's evisceration of the due process protections accorded them through the Amendments to the United States' Constitution, during the post 9/11 era. While quite extreme, these examples merely illustrate the reality that environmental circumstances will have a profound effect on the human psyche. Logic would predict that the more subtle the environmental influence, the more nuanced the effect on people's thought processes, but it would be a stretch to imagine the absence of such effect.

Adding to the melee of societal standards, the influences of our upbringing and other human factors that come into play during our formative years and our environmental circumstances, our natures, or genetic predispositions, must also join the mix. We are born of a genetic stew of material that determines many of our physical attributes. Race, skin tone, eye color, height, our predispositions for certain ailments and diseases are among these. So too, are we thusly affected psychologically. Nature may endow us of certain latent intellect, forge us into sociopaths, elect our propensities to fight or take flight in the face of danger, and the like, the sum of which more than likely imposes an array of parameters within which we craft our choices. Most to the point, our natural inclinations have a hand in how we act and react to all of the extrinsic stimuli that assail us from within the womb and throughout our lives.

Holistically, it is fully evident that the sum of these, nurture, environment and nature, hold sway over our freedom to choose. Quantifying the interplay between nurture, environment and nature, how one is sifted through another in forming human character, and the ability to make choices not thereby affected, represents a complexity that is frankly beyond my ken. It is sufficient to understand that neither free will, nor the choices derived therefrom, are as without hindrance as we would like to imagine. This is a direct contradiction to the quantum philosophical and, indeed, Christian, rhetoric espousing unhindered will as an engrained human characteristic, most certainly as one that serves to distinguish humans from all other creatures.

Are there conditions or other latent factors that would serve to mitigate intrusions in to one's independence of will. Would, for example, a child genetically engineered, conceived artificially and raised in a vacuum, free of all human interaction, be capable of making choices fully of its own volition. Such a hypothetical is not entirely outside the bounds of modern technology. The prospect of designer babies conceived in test tubes has surpassed mere latency and the concept of raising children in a sterile vacuum, under the care of absolute neutrals who provide only nourishment, clothing and the like, while the task of educating is is left to some form of artificial intelligence, is not inconceivable in our increasingly dystopian society. What would such a child look like at, say, the age of sixteen. To begin with, it would be socially inept. But, perhaps for purposes of pure self determination, this would be a good thing. Free of the burdens imposed by parental and social conditioning, one might expect this child to gain some independence of will. And, thereby, some purity in its freedom to choose, to make choices against a backdrop of absolute emancipation from extrinsically imposed shackles.

A problem persists, nonetheless, in this quite draconian scenario. Simply put, it is that this child, or young adult, once time has run its course, is not truly free of influences. It has been genetically engineered and is, thus, subject the concomitant “natural” influences. Further, it has been educated by machines, albeit intelligent ones, which, at their genesis, have been programmed by humans, and whose access to educational materials is dependent on archives created by the human mind, though its interpretations, as one might expect of sentient, or even quasi sentient, machines, might vary. Semantics aside, the fundamental reality would be that the product of such an upbringing, though quite likely different from its normally reared counterparts, would still have been molded by its genetic construction and the influences, whether genetic or deliberately fashioned, of its teacher. Bertrand Russell once wrote that “Men are born ignorant, not stupid. They are made stupid by education.” While I can not offer any judgement related to the quality of education that would be associated with the scenario painted in the foregoing, Russell's admonition does suggest that the empty mind of birth is readily contaminated by those charged with fueling it.

As another hypothetical, were we to make our choices on a random basis, say with a coin toss, or even some algorithm that generates an affirmative decision as to one option of another, we are still faced with the conundrum that the array of choices we have generated are still firmly embedded within the boundaries dictated by all of our predispositions,

Sociopathy presents another avenue of potential freedom from intrusions into free will and, thereby, the crafting of freely made choices. But again, this is not an absolute. Sociopaths, a categorization which includes psychopaths, a term now deemed arguably archaic, are generally defined as people having an anti-social personality disorder. As such, and without exploring whether those subject to the condition are incapable of distinguishing right from wrong, or simply elect amorality, sociopaths act in accord with their wishes, with total disregard for whether their conduct exceeds the cope of societal mores, codified or not. According to the Mayo Clinic, sociopathy may be the result of genetics, sometimes triggered by environmental issues, or altered brain functions.

A sociopath, for whichever of these reasons one accepts, is ultimately free, psychologically, to make choices without any inherent inhibitions as to whether these are societally acceptable or not. Those decisions, however, are still molded through the effects of other genetic influences and the nature of the nurture they were subjected to in growing up. So too will environmental conditions continue to fashion the actions and reactions of sociopaths to specific situations that give rise to the need to make decisions. Indeed, it is widely accepted that many sociopaths, in whom empathy is simply nonexistent, will mimic the behavior of others in order to themselves fit in or appear normal and thus artificially conform their behavior, their choices as how to act, thereby allowing their freedom to act to be controlled by the perceived expectations of others.

Friedrich Nietzsche, the philosopher, articulated the notion that free will is a fiction; that this is evidenced by the advent of birth, a matter in which the individual has absolutely no choice. Once thrust into this plain of existence, however, Nietzsche had other ideas. He posited that humankind is incapable of intellectual growth, an inability to which he attributed the repetitive cycles of human history, and would remain so because of its blind acceptance of, and adherence to, institutionally derived morality. Conjunctively, Nietzsche was of mind that any ability on the part of humans to develop free will, and thus be in a position to choose freely, was predicated upon casting aside institutional morality and having the fortitude to embrace self-realization in order to identify and purge the ever lingering effects of nature, nurture and environment. This, he held, would free the mind to grow to its latent potential and lay the foundation for the election of freely made choices. The manifestation of any person undertaking such an intellectual metamorphosis would, of course, be characterized as Nietzsche's oft maligned Übermensch, or Superhuman.

Some might argue that human models for Nietzsche's Superhuman have been manifest in the personae of people such as members of our political elite, on both sides of the aisle, or modern oligarchs, such as Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Sundar Pichai and Jack Dorsey, to name but few of many. However, I would suggest that this characterization represents a complete misunderstanding of the concept by confusing power to mean dominion, rather than self realization and determinism. Ultimately, these people tend to consider their actions above the moral standards most of us are societally confined to, rather than intellectually beyond them. This position is buttressed by their openly displayed, narcissistic tendencies, utter ruthlessness and lack of any interests, save self interests, and ongoing campaigns to use monetary largesse, formed as highly controlled donations, in efforts to “normalize” themselves. If these traits seem familiar, it is because they define sociopathy, rather than the achievement of moral transcendence.

Nietzsche's Superhuman should not be mistaken as a sociopath. This evolved being would not be immoral. Instead, such a person would be completely amoral as to the effects of institutionalized morality, from wherever derived, and its sole font of morality would be found in nature. Not the divinely rooted laws of nature espoused by John Locke and Thomas Jefferson, but, instead, Nietzsche saw morality as an inherent condition of nature to which all living things gain a subscription at birth. As such, he saw the state of nature being ordered through assessments of good and bad, and viewed all humanly imposed morality as the presentation of evil, as the antithesis of good and, thereby, an artifice to be rejected. To Nietzsche, and this is perhaps where many have run afoul of understanding his ideas, good is born of power, while bad is that which is borne of weakness. Power, in his view, in spite of its common definitions to the contrary, is not a matter of dominion over others. Rather, it lies in the elimination of self delusion by evaluating oneself truthfully, seeking knowledge and assessing it honestly, all with the goal of not only improving the self, which Nietzsche believed must be realized, or even reconstructed after birth, through conscious effort and self discipline, but also of achieving self determination, absent extraneous clutter and the contaminating effects of institutionalized moral doctrine. Self delusion, in his paradigm, requires occasional interruption by illusion, in the form of arts, to gain reprieve from personal and environmental realities. Nietzsche also held that in order to become true to the self and realize self determination, all orthodoxy bears questioning, rather than faithful acceptance. It is worth noting that Nietzsche was influenced by philosophical Taoism and it is against this backdrop that his works ought be considered.

It was Adolph Hitler's perverse distortion of Nietzsche's Superhuman, as an ideal, that undermined the latter's ideas which, in and of itself, is somewhat ironic. Had they existed contemporaneously, Hitler would have likely put Nietzsche to death, given Nietzsche's abhorrence of authoritarianism, which he saw as utterly antithetical to humankind's pressing need to better itself. This said, Nietzsche was not an advocate of anarchy, any more than were John Locke and Thomas Jefferson. The distinguishing feature is that the former sought to strip away the very foundational concept of natural law upon which the likes of Locke and Jefferson so heavily relied, by replacing it with a mandatory quest, whereby humanity is embarked on a pure objective of gaining truth and knowledge to an extent that, if achieved, would create a completely novel societal paradigm based upon critical thinking.

Of critical importance, Nietzsche's advocation was directed towards a shift in the societal paradigm, rather than a mere handful of individuals. He was, I think quite rightfully, persuaded that only evolution of a prevalent class of super humans would allow reshaping of humanity's course into the future. Implicitly and, it would seem, obviously, the emergence of sporadic instances of the ideal person, the Übermensch, would not only be incapable of forging societal change, but would likely be deemed anomalous and thus socially alienated. Alas, poor Nietzsche! His error, of grave magnitude, lay in failing to truly understand his fellow beings. The human herd is, by and large, intellectually and physically prone to laziness; we are, collectively speaking, utterly inclined to elect the path of least resistance. Hence, the human saga has evolved a propensity for pursuing technological improvement to facilitate its endeavors, regardless of consequence, and casting aside most notions of intellectual growth, save those necessary for pursuit of the various grails technological. Our species is, I would unabashedly argue, although there are admittedly certain exceptions, Cro-Magnon equipped with some pretty damn sophisticated spears and communication devices. Sacrilege perhaps, but true nonetheless. Indeed, as has been borne out by some studies, modern man is a social creature with every inclination to move as a herd and, when we do so, it seems that we operate in accord with an intelligence quotient that is some three points less than that of the lowest common denominator found within the herd. Based upon history and personal experience, I find it difficult to disagree with this premise.

Moral edicts, or expected practices, in other forms, are integral aspects of societal expectations. Whether weddings, wakes and funerals, ultimately forms of wealth redistribution that have become rituals, or, in conjunction with State and Church, promotion of the view that it is the obligation of every able bodied citizen to produce and consume in order to be deemed a worthy member of society, the scope of institutionalized morality is such that it permeates every aspect of our beings, physically and psychologically, from cradle to grave.

In contemplating institutionalized morality, we should not merely confine ourselves to the obvious, such as governmental edicts and religious doctrine mandating that actions require temperance to stay within moral paradigms, but must also include the bar on certain thoughts that breach the boundaries of institutional dogma. Such are exemplified by four of the seven deadly sins found in Catholicism, lust, wrath, envy and pride, as modified from the original of these by the Catholic Pope, Gregory the First, in AD 590. So too, have States long cautioned against impure thoughts that denigrate their legitimacy.

Nor are thoughts and ideas, and the expression of these, free of the ambitions of societal engineers – these not necessarily comprised of any majority, but often indicative of the political weight granted the wealthy or the most clamorous – though these two groups are unlikely to be operating with the same long term objectives in mind. Hence, we might have one group, the first, striving to mold a malleable society that will eventually accept, seemingly benevolent, techno-totalitarianism; a world in which everyone is employed by large corporations, the state, or is a dependent of the state, in which there are no small or medium sized businesses, digital credit systems replace currency and we eventually evolve into a two class society, comprised of those in control and those who are not. Coincidently, or not, this may well become the ambition of governments, unable to meet the rising demand for economic security, while lacking the means to pay therefore. This, while the second group might be embarked on moving a society towards its vision of a utopian ideal, something only achievable by purging contrarian notions. The common thread among these two sets, which bodes poorly for the possibility of Nietzsche's super human, is the specter of absolute failure if the concept of critical thinking, in the traditional sense, is not somehow rendered obsolete. Absolute acceptance of any freshly devised social paradigm is, after all, essential to its success. The present trends towards “technological dependency” “woke-ism, “cancel culture” and “extremist right wing rhetoric” fall squarely within these parameters, which are, at heart, no different than the assaults mounted on the free expression of ideas by the Catholic Church during Europe's Dark Ages.

It merits suggesting, at this juncture, given the circumstances of our existence, that the fortitude and prowess of any person to identify and correct, for wont of a better term, the implications of genetics, nurture and environment on one's being, with the goal of becoming truly become free, one must already be a super human. Unfortunately, societal introspection seems an unlikely mission for a species incapable, from one generation to the next, never mind over the longer term, of identifying and then avoiding the mistakes of history, whether individual or generational, no matter how objectively curated. Hence, in spite of personally believing in the benefits of actualizing the full latency of human intellectual capability, the idea falters at the onset as a utopian ideal that grows increasingly unlikely to be realized. This becomes a certainty in the face of declining educational standards and the advances and human reliance on technologies, together with the affronts to individual and societal liberty interests these embody.

Subliminal advertising, once said to permeate television ads, has morphed into a reality of algorithms which, based upon our internet searches and social media patterns, ostensibly determine our proclivities, whether the food we like, the cars we admire or our darker desires, and fashion individualized ad campaigns, designed to have us act on all of these. Hence, we are herded into choices we might otherwise not have made. Our daily activities are recorded for posterity by our mobile devices, car cameras and black boxes, computers and the ubiquitous Alexa, and its ilk, and then sold to government agencies and large corporate merchants. And we acquiesce to these intrusions, blissfully unaware that no good can come of this; our conversion to useful commodities whose habits may be directed and who may also be deemed useless for their dearth of conformity. Most importantly, should we refuse to avail ourselves of the bulk of these technologies, particularly in our employment and business endeavors, we doom ourselves to almost certain failure because of the handicap suffered by going it alone, so to speak. All of this represents a situational reality that, although still, in objective terms, a matter of choices, denudes our freedom because if we opt out, our quality of life is adversely affected.

Finally, it seems germane to offer a few brief words on education and its significance on the specter of freedom. While all of the foregoing is representative of a baseline, if you will, regarding factors that affect freedom, the demise of education as a vehicle for attaining the skill of critical thinking serves to further diminish our capacity to realize freedom, both in our thoughts and our actions, or choices. Critical thinking, as an educational philosophy, often coined as a classical liberal foundation, involved nothing more than teaching a broad array of subjects, perhaps including maths; sciences; geography; languages; philosophy; and, contextual history, defined as not merely revisiting the past, from an objective rather than revisionist stance, but also exploring the questions of all of the circumstances surrounding specific events of the past. As to history, the modernly acceptable mantra, that in this present enlightened age the past will never be repeated, is a sentiment oft repeated throughout the course of history, by those who saw themselves above it and then promptly succumbed to repeating the errors of their forebears. The overall objective of a critically thinking rooted educational system is not to engender in students a particular expertise in any of the subjects taught, but rather to allow development, through broad based knowledge, of an ability to apply that knowledge, together with experience and learned research skills, to parsing, understanding and ultimately accepting, or rejecting, any given set of circumstances, hypotheses or representations. The purpose of education has long shifted from this paradigm to one aimed at sating anticipated labor markets, engineering a malleable society and, above all, producing “good” citizens. The latter, quite naturally, those who neither question the state, their expected roles in society and the economy, or their circumstances. Abject conformity has, sadly, become the holy grail of our educational institutions.

The consequential impact on our liberty interests, or freedoms, are obvious, beginning with an inability to even recognize which freedoms have been institutionally curtailed and culminating in a dearth of possessing the means to objectively recognize the cumulative effects of extrinsic and natural influences upon one's latitude in exercising freedom in any fashion. Indeed, one might even suggest that this ignorance extends to an unawareness of even those freedoms that have been institutionally granted, many of our frustrations directed at these, rather than the nuances of the bigger picture. Thus, in the United States, for example, on an exponentially increasing basis, we see championing of the rights we have to openly express our own views, while we mount assaults, on grounds of some perceived right, to silence those who disagree with us, in an absolute vacuum of any notion that were we to succeed, so too, in the not too distance future, would we be silenced as well. The irony is unmistakable; that we would destroy a rare and fragile thread of a freedom we enjoy, in order to deny it to someone else. And, all the while, we remain ignorant of the fact that the true nature of the freedoms denied us are otherwise institutionalized, with our full support, or are to be found deep within ourselves.

We rail agains the slavery of the past, long illegal in every western country, though not in the Peoples Republic of China, from whom we have no qualms in acquiring consumer goods, and other countries, such as Saudi Arabia and Libya, while ignoring the effects of domestic, institutionalized racism, now prevalent through the auspices of malaise in our educational curricula and welfare mechanics that punish those who try to escape its requirement for long term dependancy. Freedom once won, in this instance, succumbing to its present absence.

Even the most educated of us, are subject to flaws in our abilities to think critically outside the scope of our focus. One of the most noteworthy examples of this is Albert Einstein's admonition, offered in reaction to the quantum theory of entanglement, that “God doesn't play dice.” This, in spite of the fact that no empirical data exists to validate the existence of any deity, never mind one of sentience, as implied by Einstein.

Ultimately, the absence of critical thinking exacerbates the role of nurture in our abilities, or failings therein, to make free choices and it is a handicap that is passed down generationally. In fact, I would go so far as to suggest that it is beyond recovery as a realizable concept. To put it more aptly, if the teacher is incapable of thinking critically, how is the student to learn its principles.

And now, to the crux of the matter, of whether we are free. As stated at the onset, “freedom” has found its way into the vernacular of most, if not all, cultures. This said, though perhaps akin to dancing on the head of a pin, it is worthwhile pointing out that the very concept of freedom held by each of us, whether in the United States, Gambia or one of the Koreas, is a concept that, in and of itself, is the product of all of the constraints that have been explored in the preceding pages. Logically, then, my definition of freedom may very well, and likely does, differ from yours, or that of people from other parts of the world.

Colin Kaepernick, for example, a player for the National Football League (NFL), most noted for his protests during games, and who earned some 45 million dollars between 2011 and the present, likened the NFL's draft process, whereby players are chosen to play on specific teams, to slavery, no different than that experienced by African Americans during the era when slavery was legal. From my perspective, this notion is somewhat disingenuous and one wonders whether those sold into slavery on the auction blocks of yore, and even those sold similarly in Libya today, would agree with Mr. Kaepernick. This said, it is his take, predicated upon the sum of the influences on his being, that his freedom was vitiated by the processes he was required to undergo in order to play the game.

Some people I have encountered perceive freedom as achievable by moving to the center of the societal universe and requiring everything within their spheres of influence to revolve around themselves, accepting those and that which pleases them, while rejecting those and that which do not. My view on this is that this is less an indicia of freedom, than it is a new norm of behavior that is emerging, an age of narcissism, brought about by the influences of technology that allow people to shield themselves from the consequences of their words and actions. This akin to being emotionally detached from the wars we have sent our soldiers to fight because we, save family members of our warriors, are largely unaware of these conflicts and not directly impacted by them unless by virtue of noticing something on the television. Indeed, our burgeoning self indulgence is more a trap that determines our conduct, as a byproduct of social conditioning, than it is the opening of any door through which we might escape to realize freedom.

All of this suggests that none of us are truly free to describe the meaning of “freedom,” or what it means to be free. It embodies a definition, or just a fleeting recognition, that is formed within us by nature, nurture, our environment, and and ability to grasp the concept and define it within those confines. Given this, I will attempt to answer the question from the only perspective that I am qualified to, my own. Others, I can only suggest, including those taking the time to read this essay, must find their own answers.

My take on the matter is that freedom is nebulous, at best. It is, perhaps, analogous to the freedom enjoyed by soccer players; they are free to play as they choose, provided the game is played within the physical parameters of the field and within the scope of its ample array of rules. So too, is play affected by the elements and abilities of individual players, their inclination towards team ship and their states of mind. Our footballers are on the field because they choose to be, yet their choice is one representative of the culmination of influences beyond their control.

Ultimately, my belief, or sense of the freedom, as a holistic thing is that I am not free, except to play within the paradigms that have been allotted me by my nature; my upbringing; the extrinsic influences on my life, institutional and otherwise; the environment in which I find myself; and a myriad of other factors over which I have no control, or even awareness. Yet, I do have choices. And, while colored through all of the foregoing, they are mine to make and I have consistently done so. And in this, I have found both great joy, as well as misery. So too, as I grow older and more aware, have I identified those factors that impugn my freedom to the extent I resent them; production and consumption; elitism; the meaninglessness of meritocracy; the recognition that I am relegated to the role of vassal, not liege; and, above all else, in this heavily faltering socio-political and economic system of ours, that the illusion of the freedoms I thought were real, are being shattered and rendered into a multitude of shards, each a mockery of that which I believed to be true.

My response, then, to this turn of events, and perhaps driven by yet another series of factors, both recognizable and unbeknown to me, is to rebel. To reject the paradigm to which I have been enthralled throughout my life and forge a path that, at minimum, is borne of my knowledge that my ability to think is what will allow me to push the boundaries of that which has been preordained. To seek a modicum of true freedom.

My first such endeavor, the writing of this essay.